Civics education: a pre-election update

What, if anything, has changed regarding civics education in the five years since I wrote a book about it?

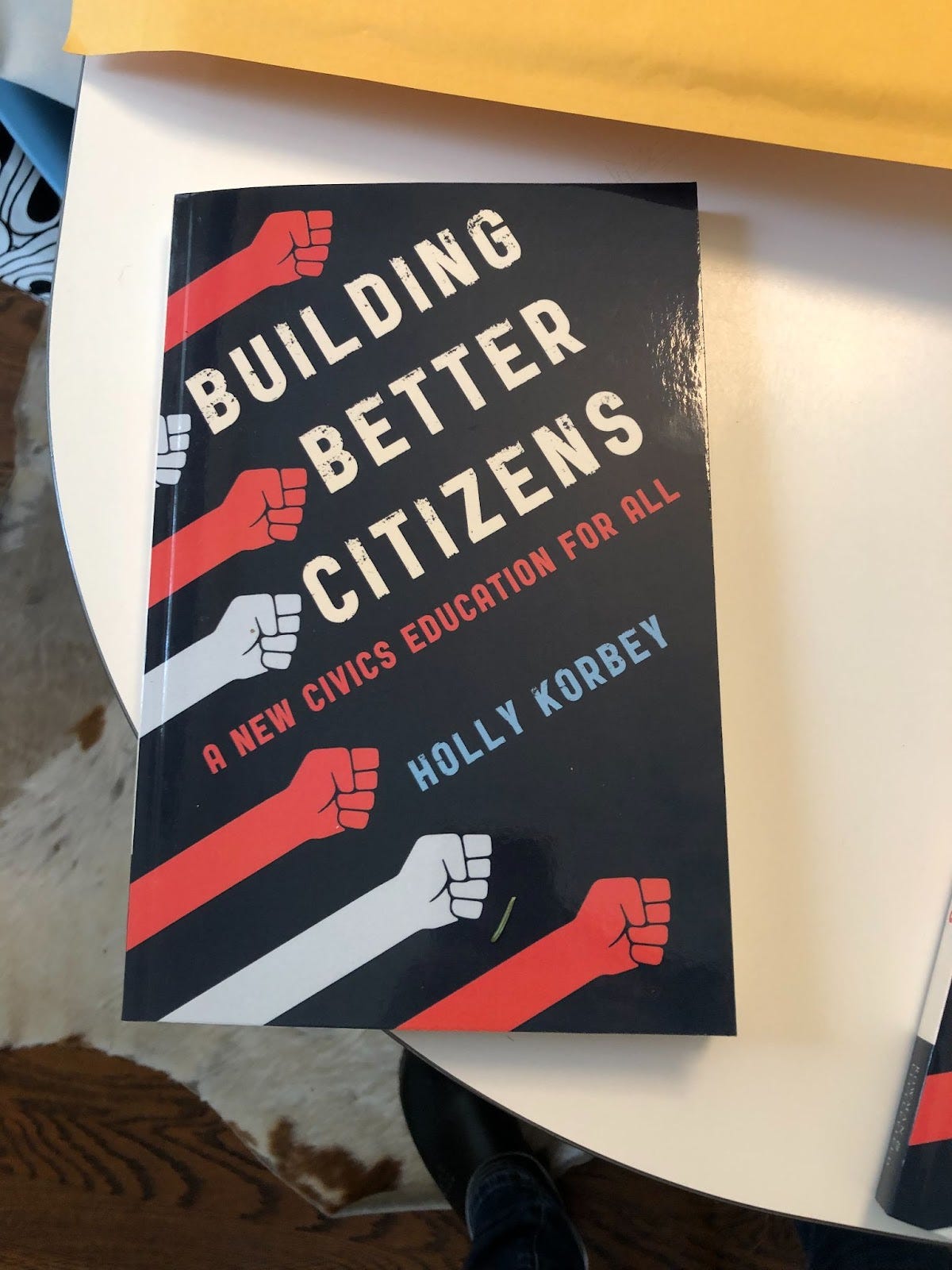

Five years ago this week, my first (and so far only) book, Building Better Citizens: A New Civics Education for All, was published. Since there’s another big election coming up—you may or may not be aware (I kid!)—I thought I’d take a look at what has or hasn’t happened since I wrote it. Has anything changed in civics? Has the more and better civics education that advocates were clamoring for in 2017 and 2018 made its way into schools? Has it made a difference to kids?

Educating students to be participants in democracy was the original reason for launching the American public school system. A lot of experts and educators still believe today that a civic education—also known as how to be a knowledgeable and engaged citizen in a representative democracy—should be one of school’s main functions, even as there are increasing arguments over what that should look like, where to fit it in among all the requirements, not to mention who is being biased against who, what history is being left out, etc. Around the time the book was published in late October of 2019, there was a lot of media and talk among schools about a civics resurgence. But almost immediately after that momentum began there was a counterpoint backlash, with a rush of laws passed in more than 35 states restricting what schools could discuss about history and politics, among other things.

I’m not entirely sure whether this civics resurgence ever got off the ground as a national movement. So many schools have been such a sh*tshow regarding civics that political scientists like Lindsey Cormack have suggested in her book How to Raise a Citizen that it might be more helpful to kids if parents take it on at home.

So what do I mean by civics education? Generally history, government and politics, but also giving students some in-person experiences interacting with government and politics—whether that means Model UN and Youth in Government-type programs, debate, action civics or mock legislature.

One of civics’ biggest issues in getting attention, in my humble opinion, is that it’s hard to define, so therefore hard to fit inside a box, which is often crucial for big school systems. There are few state exams that test civic knowledge explicitly, and a few more that make a civics capstone project part of a graduation requirement, though the expectations are wide-ranging and nebulous. Experts including Cormack have told me that a one-off class your senior year of high school, usually a government class, isn’t really going to cut it to make sure kids not just cover but understand the constitution, how the electoral college works, how the judicial system functions, etc. The one-semester course is the greatest hits version; welcome, because it’s better than nothing, but not getting the job done.

Building Better Citizens’ thesis goes something like this: the divisive and hateful presidential election of 2016 pushed a lot of educators, experts, advocates and students to start talking more forcefully about something they’d been noticing for years: there wasn’t much civics education at school. They used the 2016 election as their proof. There was a sense that civics was once a much bigger part of school, but had slowly been chipped away, as more effort was put into reading and math and the standardized tests for both, and demand for more STEM education. But a grassroots movement, coming from the bottom up—teachers and principals worried at how little their students knew about how the government worked, perhaps egged on by hearing about what kids’ knew about politics and government based on their social media diets, which is where most students got their information—wanted to beef up civics, but also expand what it included, a more “21st Century” version that addressed big issues like low-voter participation among the youngest citizens, and how on earth to help kids understand the information they were getting from the internet, much of it manipulated, distorted, and wrong.

Many of the book’s chapters take a look at some innovations and grassroots movements that were making a splash at the time: the Parkland activists that learned about both gun laws and the history of protest from their AP Government class; the cognitive science on how ‘background knowledge’ improves reading comprehension, basic knowledge about the world and critical thinking, especially as applied to history class, due in large part to the popularity of Natalie Wexler’s book The Knowledge Gap; how nonprofits like Generation Citizen were attempting to transform what they saw as a dry and boring senior government requirement into something more active, through teaching students how to engage, lobby and persuade their local government to solve real issues in their neighborhoods and communities.

I looked at the research, too, especially what was available at the time on measuring which educational measures ended up being correlated to producing more civically engaged adults. The strongest indicators of future engaged citizens are still correlated to the education level of your family, and whether your family votes and volunteers in the community. There’s some interesting but murkier evidence about the effects of comprehensive history curriculum, talking about politics and controversial topics in class (with guardrails and a trained teacher), mock elections, service learning and community volunteering, plus a few more. I also wrote about some then-new research, strong experimental stuff, from the Stanford History Education Group, now called the Digital Inquiry Group, on how to teach students the difference between true and false on the internet.

If you’re interested, you can check out the book here.

So where are we with civics now?

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to The Bell Ringer to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.