Natalie Wexler: There's a blind spot in the science of learning

A video interview with The Knowledge Gap author about her new book

Welcome back, Bell Ringers. Big day! We’ve got a 45-minute video interview with journalist and author Natalie Wexler teed up and ready for you, about how a bigger slice of reading instruction should be connected to the principles of the science of learning. “We’re making reading harder than it needs to be,” Wexler told me in this interview.

Free subscribers get an excerpt of our chat in this letter, but paying subscribers are going to get to see and hear the whole thing. Would love for you to join us behind the paywall!

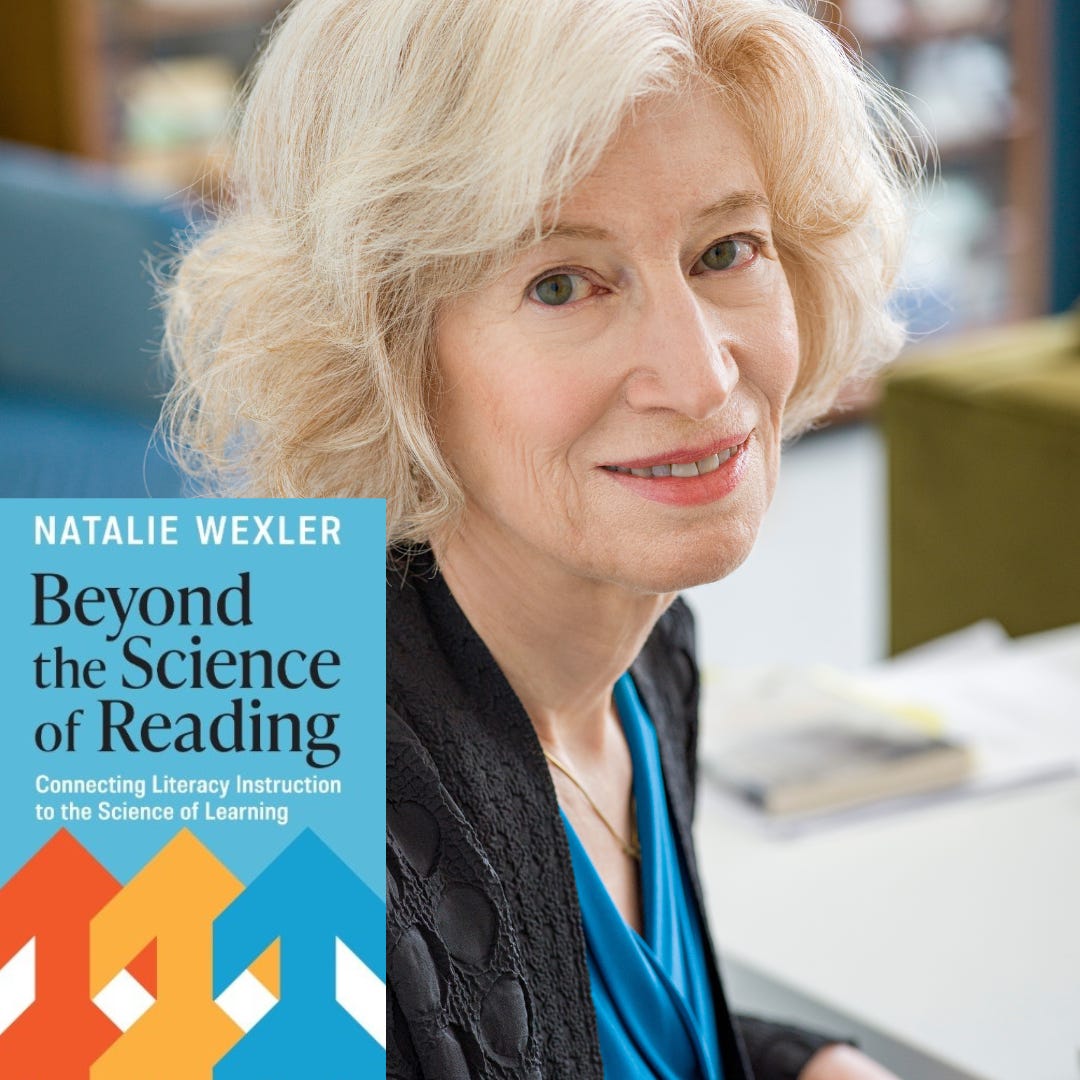

You may know Wexler from her work at The Atlantic or The New York Times, or her wildly popular evidence-based books like The Writing Revolution or The Knowledge Gap. She also has a Substack called Minding the Gap that I read and share on the regular because it's consistently about evidence-based instruction.

The science of reading ushered in a new wave of attention to evidence-based practices in reading instruction. But that attention has been almost exclusively dedicated to phonics, Wexler says. Phonics is crucial to decoding, but more attention needs to be paid—especially in the growing “science of learning” movement—to what happens after students learn to decode, and they begin reading for learning and understanding.

Understanding the cognitive science of teaching and learning also applies to reading comprehension and writing, Wexler argues in her new book, Beyond the Science of Reading: Connecting Literacy Instruction to the Science of Learning, published on January 21—and she feels that’s a blind spot in the growing science of learning movement.

Keep reading—excerpt and full interview below!

What to read next

Last week’s post, which took an evidence-based look at what classrooms and teachers can do to get kids reading more books, generated some great ideas and helpful comments from readers.

High school history teacher Jenna Vandenberg, who writes the Substack Jenna Repeats History, said she’s been using the last 5 minutes of world history class for reading historical fiction aloud to her students:

Reader Miriam Fein noted that often teachers of older students don’t know how well their students read, because for a variety of reasons, students don’t do much reading aloud in middle and high school. It might be poor reading skill, not lack of desire, that’s keeping students from books, she suggested:

Reader Mike G suggested that ELA tests could be designed differently—with book reading as a requirement, forcing schools to teach kids how to read books in order to do well on the test:

Want to learn more? Read the entire post here.

There’s a blind spot in the science of learning: an interview with Natalie Wexler

Here’s an excerpt from the interview (or skip to the full video interview, below):

Holly Korbey: When I started reading your book, the first thing I thought about is that in my everyday conversations, when I bring up the words “science of learning,” it is confusing to a lot of people, even in the education world. Do you mean the science of reading? Or, That must have to do with reading and not with math? And we're in this moment where, when we talk about evidence on teaching and learning, it's almost like it's a bunch of separate things, separated by subject content.

But your new book asks readers to look at things in a different way—that the science of reading connects to and is actually a part of this larger body of evidence on how humans learn generally. So my first thought is: what were you seeing or observing or thinking about that even made you wonder, hey, how are these two things connected?

Natalie Wexler: Well, I've had for the last several years a foot in sort of two worlds, one foot in the science of reading world, one foot in the science of learning world, or cognitive science. I've gone to conferences like researchED, which are designed to bring principles of cognitive science to teachers who often don't learn about those things during their training or even after. So there's several reasons I wrote this book.

But one reason was that I think this researchED movement, the science of learning movement is terrific, but there seemed to be this sort of blind spot. They weren't talking about literacy instruction, except insofar as it relates to phonics and decoding. Nobody was really talking about the way schools have been teaching reading comprehension, and whether that lines up with cognitive science, or talking about writing.

I never see anything about writing. Most of the studies we have from cognitive scientists focus on math or science or some substantive content area.

And one thing that I realized is if you are a literacy teacher or reading teacher and you want to apply the principles that are backed by cognitive science to your instruction, you really can't—because those principles assume that you're either teaching actual substance like history or science, or that you're teaching a transferable skill like decoding words. But when you're teaching comprehension skills, you're actually trying to teach non-transferable skills, which is kind of what my book The Knowledge Gap is all about.

But something like making inferences—I mean, yes, kids do need to learn how to make inferences when they read, but it's taught as though it was this sort of abstract skill that you can teach directly and then kids will apply generally. So if they practice making inferences on some very simple text, they'll master the skill of making inferences and they'll be able to make inferences about more complex text.

But no, actually—and I think it's kind of common sense—if you're reading a book on a topic that you know really well, it's a lot easier to make inferences than if you're reading a complex text on some subject you don't know anything about.

So something like retrieval practice, which is very powerful—you know, it's this principle that if you practice retrieving an item of information that you've got somewhere in long-term memory, the more you practice retrieving that item of information, the more likely you are to be able to retrieve it in the future. And that sort of lays the foundation for higher order thinking, analysis, et cetera, and learning more about that topic.

But if you're teaching making inferences, what do you have kids practice retrieving? It doesn't make sense to just retrieve “making inferences.” And then if you've got 25 kids reading books on 25 different topics, you're not trying to teach any common content. You can’t have them practice retrieving any common content.

One reason I wrote the book: I want both teachers of reading and people in the cognitive science, science of learning movement to understand that there's this kind of disconnect. Even if you discover principles like retrieval practice as an elementary teacher, you're spending half your instructional time teaching stuff that you cannot apply these principles to.

Holly Korbey: What you talk about early on in the book is that within the science of reading, phonics instruction has kind of sucked the air out of the room, as far as evidence-based practices are concerned. But that's really only a piece of making a fluent reader and teaching reading comprehension. It’s not a very straightforward thing to teach at all.

So these cognitive science principles are—they can help with reading comprehension and writing, but you have to look at it in a different way.

Natalie Wexler: Absolutely, and I do think we need to get away from the idea of teaching reading comprehension as something that's separate from teaching content. It's a little complicated, but because I think there are different reading comprehension skills that maybe require different approaches.

One of the messages I hope that people will take from this book is that all of this stuff is connected and that every literacy teacher should also be a content area teacher, and vice versa.

Every content area teacher should also be thinking: if you're teaching science, if you're teaching history, you should be thinking about what vocabulary do these kids need to know, and what do they need to retain? What about this reading passage or this chapter, what kind of support do they need? Every subject can benefit from writing. Another message I'd like to get across is that writing is probably our best way of teaching a lot of the things that we try to teach through teaching reading comprehension strategies, like finding the main idea, which is pretty much the same as summarizing.

And rather than just saying to kids—and I've heard this from teachers, this is often the way finding the main idea or summarizing is taught—you just tell kids, well, just focus on the important things and leave out the unimportant things. But many kids need more guidance than that. And so through writing, can provide that kind of structure, that kind of guidance.

I would love there to be more research on writing done through a cognitive science lens. But we do have studies that are cognitive science studies showing that writing can be a very powerful form of retrieval practice…

Watch the full video below!

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to The Bell Ringer to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.