Is the 'Louisiana Miracle' next? Plus a new Tools for Practice

A chemistry teacher uses the science of learning for a better lab experience

Welcome, Bell Ringers, to the only artisanally handcrafted newsletter focused on news, tools and resources for the science of learning. I’m so happy you’re here. If you’ve ever wondered what’s happening behind the paywall, and want to join the comments discussion and get access to the full archive, try it out for seven days here:

Today’s letter looks at how learning science and high-quality curriculum became part of the formula that helped Louisiana’s recent success in NAEP reading scores. *PLUS* a new Tools for Practice from a high school chemistry teacher who used the foundations of cognitive science to transform her lab procedures—and students are learning more chemistry.

Experts say teacher training, curriculum might spur Louisiana’s own reading miracle

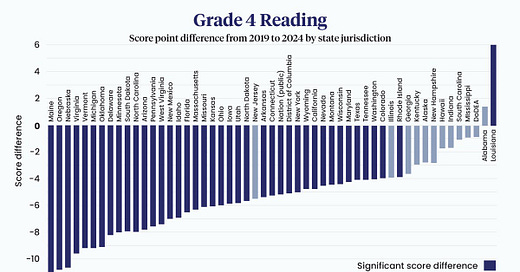

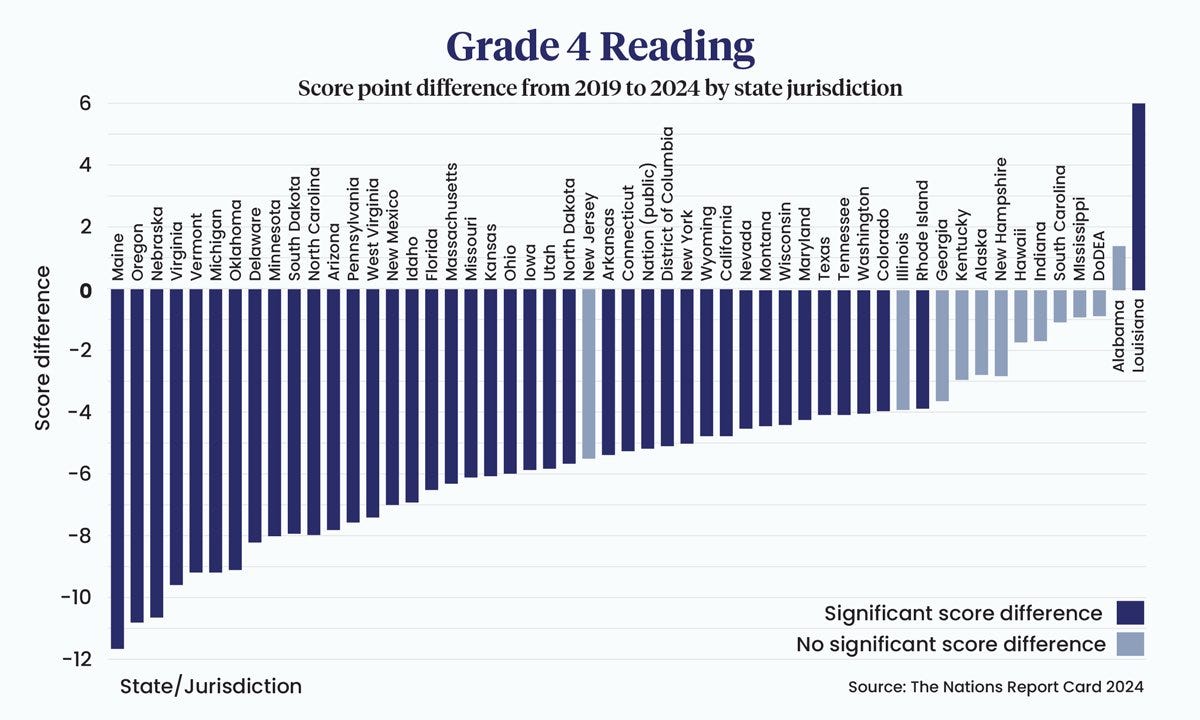

As everyone in education expected, the 2024 Nation’s Report Card exam scores, the National Assessment for Education Progress, continued to show a national decline in student reading and math skills, widening the gap between the highest- and lowest-performing students. Average reading scores for 8th graders in 2024 were five points below what they were in 2019; scores dropped 8 points in math from the same time period. Core losses were greater for lower-performing students; the number of students who scored in the lowest category, ‘Below Basic,’ grew in 2024, to one in three, or 33%—more students than when the test was first conducted in 1992.

While math scores have improved slightly since 2022—8th graders scored two points higher on average in math in 2024 compared to two years ago—the number of students who fall into the lowest scoring category, ‘Below Basic,’ grew to 39%.

“Certainly the most striking thing in the results is the increase in inequality,” is how Harvard professor Martin West, vice chair of the National Assessment Governing Board that oversees the exam (and also my sometimes editor at Education Next), put it to Jill Barshay at The Hechinger Report. “What we may be seeing now are the enduring consequences of gaps in basic skills. As the gaps accumulate, it becomes harder and harder for students to keep up with grade-level content.”

As hard as these numbers look, there are bright spots. My home state of Indiana, which has recently invested heavily in training teachers in the science of reading, jumped in ranking in both fourth and eighth grade reading to 6th in the nation, from 17th and 19th, respectively. Mississippi, which has made great strides in reading over the last decade, made little progress from 2022, but also held steady while nearly every other state’s scores declined.

But all eyes are on Louisiana, which led the nation in reading growth in 2024, meeting the national average for the first time in the test’s history.

Louisiana has followed in the footsteps of other states who have seen recent improvement like Mississippi, Tennessee and Alabama. They’ve put accountability measures in place, invested in teacher training and coaching as well as in high-quality materials.

Just like in other states seeing success, teacher training in structured literacy seems to be playing a significant role in student gains. A 2021 Louisiana law required not just k-3 educators but also school leaders to get trained in both how the brain learns to read and how that changes reading instruction, and results are beginning to show.

Many Louisiana schools trained principals, assistant principals and instructional coaches either first or alongside teachers, which was key to progress, representatives at the AIM Institute for Learning & Research told me in an interview yesterday. The AIM Institute, located outside of Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, has provided a 55-hour course training in structured literacy to nearly 10,000 Louisiana educators.

The course model, which was delivered virtually, is based on the idea of “learn, practice, apply,” with instructors asking educators to take what they learned back to classrooms immediately.

“One of our last things we say at virtual sessions is, ‘what’s your a-ha moment?’” said Carolyn Durante, senior relationship manager at AIM. “You can’t implement it all tomorrow. But you can take one thing into class tomorrow.” Those ‘one things’ build over time.

Once teachers understand the basics of the science and structured literacy, they look at curriculum differently, said independent educational consultant and teacher trainer Rod Naquin. Naquin, who serves schools throughout Louisiana, said the state’s requirement for high-quality instructional materials is only as powerful as what teachers know about the brain and what they can do with those materials.

“Things like LETRS and AIM are the rocket science of reading instruction. Teachers now have knowledge that underlies the materials they're asked to use, right?” Naquin told me. “So instead of saying, ‘Go use Core Knowledge in kinder through second grade,’ they're also growing their knowledge around the learning science that is supposed to be brought to life in those materials.”

When teachers have both, ELA classrooms looks different. Teachers are expecting both accuracy and precision in student work, Naquin said, and more classrooms are using quality texts.

“In a third grade classroom outside of Lake Charles, Louisiana, I saw where this exact thing was happening: the foundational piece is the teacher's knowledge of linguistics, letter/sound correspondence, the terminology of word parts, phonetics, phonemic awareness,” he said. “But then kids would partner up and go back to their texts and the teachers were asking intentional questions and expecting them to be precise in the way that they make a claim and refer to the text. So that's the flip.”

Reading scores are going up, Naquin said, in part because the state has thought about improvement in a comprehensive way. “In my view, it's a pretty coherent way to think about the training, the materials, the learner, learning science, job-embeddedness, the materials you're using today, tomorrow, next week,” he said. “They built an amazing thing—you can't weasel out of it. I know that sounds kind of strange, but you can’t escape it.”

States like Mississippi and Tennessee that have also seen recent reading success have created similar “closed loops” of training and curriculum, requiring districts to choose from a list of approved choices all supported by evidence.

* Read up on The Bell Ringer interviews with experts on their latest science of learning books:

* Dr Zach Groshell on the art and science of explicit teaching

* Blake Harvard on the science behind harnessing student attention

* Natalie Wexler on how the science of learning can make ELA better

Tools for Practice: Designing a deeper chemistry lab experience with cognitive science

The problem:

When high school chemistry teacher Marcie Samayoa returned to her classroom at a Title I school in Los Angeles, California, after Covid school closures, she soon became anxious and stressed out. Students, many of them English learners, were so far behind in their skills, she worried they wouldn’t catch up.

“I was so close to saying, you know what? I quit. I got anxiety every single time I walked into my room,” Samayoa said. “I’m putting in my all, and students are still not learning, you know? It's very discouraging as a teacher.”

She’d been dutifully following both her training and the directives of her high school, which were focused on the Next Generation Science Standards, which advocates for a discovery-based, inquiry approach to chemistry. But in her free time, Samayoa had been doing some digging, reading books on cognitive science principles of learning, and she decided to make a big switch, to what she called “a more traditional approach” to teaching and learning.

One area she wanted to work on was performing labs. Student labs in chemistry can often be a problem, Samayoa said. While NGSS standards claimed students would learn more from inquiry-based labs with little instruction or guidance, what Samayoa often saw in labs that led with discovery was student confusion and sometimes chaos. She didn’t believe that students were learning as much as they could.

So she re-designed the chemistry lab putting cognitive science principles out in front.

The Intervention