When the evidence isn't enough

One parent activist shares why some California districts are resisting—and undermining—the science of reading

Happy Friday, Bell Ringers! “How to think about this” journalism takes time and resources. I started this newsletter to bring you what I thought was the most important news and information about teaching and learning—so thank you, thank you for supporting The Bell Ringer.

If you’re still thinking about joining us as a paying subscriber, you can give it a try with a free 7-day trial. You get the Resource Guide and Tools for Practice for educators, plus the full archive.

Today’s big story: a recent interview with parent activist and Reading for Berkeley founder Lindsay Nofelt revealed some difficult truths about getting more kids reading in school. Nofelt reached out to me because she wanted to share an important thesis about why Berkeley Unified School District, located in Berkeley, California, is digging their heels in on balanced literacy, and her growing overall view that school power structures—ones that were meant to provide local control, and a balanced perspective—are becoming impassable obstacles to evidence-based reading reform in arguably one of the most equity-focused districts in the country.

Nofelt is the second Bay Area parent who has wanted to talk about obstacles to teaching and learning reform—last spring I also talked with Mike Malione of Save Math, a parent group dedicated to improving math instruction in the same California area.

Last month, Nofelt messaged me: “I have this thesis about power structures in the educational system, how they are hampering change. Our teachers union has controlled school board elections for decades. So we have a weak board only interested in protecting their future electability and so they ‘bikeshed’ — inflate small issues to distract from the big ones.”

And I wanted to hear what she had to say. Keep reading to get the full story.

What to read next

* Last week’s interview with Natalie Wexler about her new book Beyond the Science of Reading gets into granular detail about the research on reading comprehension, writing and the science of learning. Wexler explains how they’re all connected, and how teachers can leverage several key anchors of the science of learning to better teach reading comprehension and writing—two important areas of literacy that have gotten less attention than phonics, at least here in the US.

Watch the entire video interview with Natalie Wexler here.

* I’ve got a new story out at TES in the UK, one of the most difficult stories I’ve had to tackle in a while. In “The evolution of ‘no excuses’ behavior approaches,” I look at how the ‘no excuses’ approach started in the US and has made its way to the UK, how it’s morphed and changed, and whether there is any reliable evidence that it works, or doesn’t work. I got to talk with some of the most successful trusts (or charters) in the UK and what they told me about how they approach behavior might surprise you. Read the story here.

Links I’m reading:

* I’m a big Peps Mccrea fan (I hope you’re subscribed to his Evidence Snacks newsletter), and this week’s letter was no different—read more about the curse of knowledge, and what research suggests educators can do to counteract that blind spot. Using his words, ‘assume the worst,’is a great way to think about it—assume that your students know much less than you think. That’s not true? Then have them prove you wrong. What’s interesting to me about a lot of cognitive science principles is how apt they are for the workplace, too—senior employees might very well assume that more junior workers know more than they actually do. Incredibly helpful stuff to help people learn more.

* New Zealand is reforming math instruction by bringing the ‘science of math’ to classrooms—and they’re having the same fights over there about how to teach math that we are having right here. Read this great story from Christina Samuels at The Hechinger Report, “New Zealand has a problem with mathematics. Can a new strategy make a difference for students?” Samuels, who is my editor at Hechinger, has hinted that she’s ready to talk to The Bell Ringer about what she learned both about how NZ is tackling math and what exactly they’re fighting over, so watch for a big post on math instruction in the next couple of weeks!

When the science isn’t enough

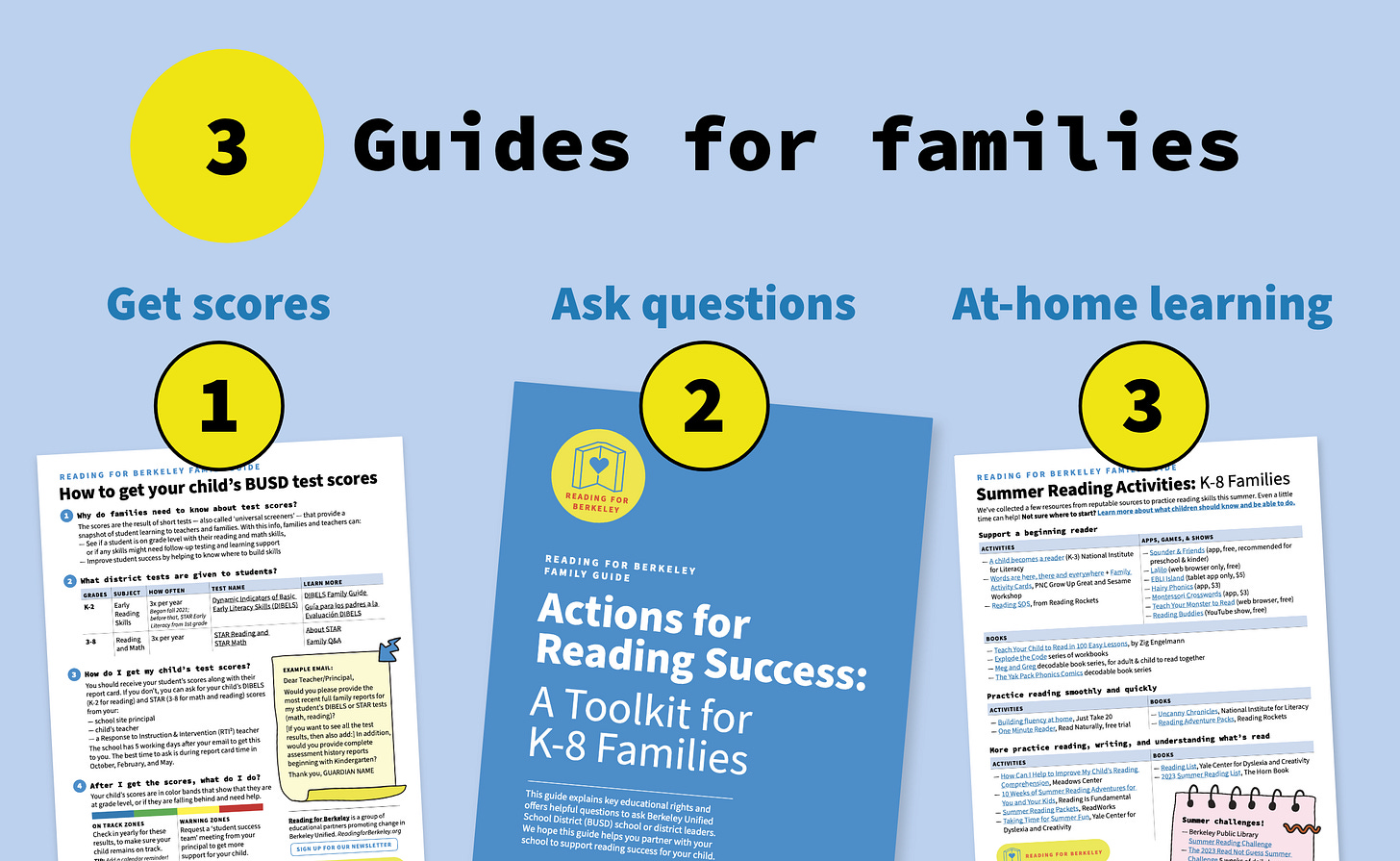

(Reading for Berkeley provides information and support to parents with struggling readers in Berkeley, California. Image courtesy of Lindsay Nofelt.)

About six years ago, when Lindsay Nofelt’s son was in kindergarten in the Berkeley Unified School District, in Berkeley, California, she noticed that he wasn’t picking up on reading in the way she expected. Like so many schools, her son’s elementary school wasn’t worried; they assured her he was fine.

Her son eventually received a dyslexia diagnosis outside of the school system, and in the ensuing years her family spent thousands of dollars—again, like so many families of struggling readers—on private tutoring in evidence-based literacy practices to get her son reading. And in the meantime, Nofelt decided to get involved with the district, hoping to alert them to her family’s experience.

“I got activated after discovering that my kid couldn't read,” Nofelt told me, “and being gaslit into thinking that he was normal and didn't need any extra help.”

Nofelt began doing a little digging, educating herself on her district’s reading scores. Thirty-three percent of Berkeley students couldn’t read at grade level, and many of those students were from disadvantaged backgrounds—low-income students who were often Black or Latino. Nofelt read about turnarounds in places like Mississippi and Tennessee, where reading reforms based on evidence were helping those very students, and began to wonder why Berkeley, with their vocal, almost obsessive commitment to equity, wasn’t following suit.

Nofelt believed bringing the district’s attention to the issue, maybe with a little pressure, would usher in reading reform. Instead, she and others found they made little headway, at one point even becoming the targets of a campaign to discredit them.

“I joined every committee known to mankind. I said, I am going to spend years just figuring out where the levers are, and where I can push,” she said. “And what I figured out after about three years is that working in the system is not that effective.”

The question for me is why? Why would a district so focused on equity resist investigating how to improve reading instruction—especially with evidence that things are improving for similar students in other places? In today’s interview with Lindsay Nofelt, she details her thesis: some of the power structures in the educational system are hampering change. Her insider view as chair of the Parent Advisory Committee, the watchdog for the Local Control Accountability Plan that she joined after Berkeley Unified settled a 2017 parent lawsuit over reading instruction, might shed some light on why some school systems don’t, won’t or can’t make necessary changes to improve—and the sometimes herculean efforts it takes to overhaul those entrenched, powerful structures.

Here’s what Lindsay Nofelt told me:

Lindsay Nofelt: I've had a few years to come to terms with our family's journey. I liken it to waking up, you know? Before, I let the educational system happen to me. And now I try to put my oar in the water a little bit more. I thought that by being an active PTA parent and always being ready with money or hands that I was, you know, ensuring that my kid could get a good education.

But within the system, you're hampered by bureaucracy. You have bylaws, you have ways to push the lever—but legally, the school has these committees to collect input, and they are not required to do anything with your input. Here in California, the most legally empowered committee is the Parent Advisory Committee for the Local Control Accountability Plan. The state requires that school districts create a plan every year with goals on how to fix the problems with their test scores, and they have to have a parent group that meets at least five times in an academic year to review the progress on the plan and to make comments and input on the new plan.

The idea for this committee is that the public parents themselves would be a check, they're going to be the accountability on whether this plan is moving forward.

The Bell Ringer: Did you join this committee?

Lindsay Nofelt: I chaired it for two years. And what I discovered is that the district only has to respond to your comments. They do not have to implement your comments. They do not have to address your comments in any real way, shape or form. And even when they do legally have to address your comments, there's no recourse for you to ask that they do a better job at it.

Every single year, the parents on this committee come together, there's a representative from every elementary school in the district, and two from middle school and three from high school. Every year we spend at least two meetings in which parents ask, Why am I here? Am I wasting my time? What kind of leverage do we have?

And the answer is: we do not actually have any leverage. What we are doing is creating a paper trail for people ahead of us to show and demonstrate that these problems have existed for decades, and basically that is the job of this committee. Do not expect change. Expect for your work to be used later on, maybe even in a lawsuit.

[Berkeley Unified parents sued the district in 2017 over issues with reading instruction, and the district settled in 2021, promising reform. Read more about that here.]

The Bell Ringer: Give me an example of one of the comments or suggestions your committee made to the accountability plan, and how it was received. What’s the nature of your communication? Does this go to the school board? Does this go to the district admin?

Lindsay Nofelt: The parent committee is overseen by someone under the assistant superintendent, they are responsible for responding to our requests as a committee and replying to the comments within three weeks after we produce them. Our comments try really hard to address the goals of the plan in a systematic way—Did you meet the goals, and if not, what are the barriers? We include what our recommendations are for change, for addressing those barriers.

We rely on parents to drive the process. So in past years, we made subcommittees that would just deal with each goal separately, because otherwise there's like 60 goals, something ridiculous, something that nobody can comprehend. The plan is 200 pages long. Nobody actually reads the entire plan, except for me!

One of the main pieces of the accountability plan is to implement Multi-Tiered Systems of Support [MTSS]. Part of the lawsuit settlement requires that the district produce and create an MTSS system. It's a big idea. It could be a foundational way to make sure that “tier one” instruction—the first teach, the main classroom instruction—is doing what it's supposed to do. But the district has done very little to implement MTSS.

And so our recommendation in 2023 was for the district to publish a strategic plan incorporating the MTSS. The response was: “Yes, of course, we have a plan!” But it has never been published. Reports on the ground are dissatisfactory. We still do not have a clear picture of how we report out the success of intervention, how schools and children are being supported, and if we truly are moving away from the “wait to fail” model, where you have to prove that you are behind by two grade levels before you qualify for any additional support, and are actively encouraged not to file for a special education assessment.

The Bell Ringer: When you asked for a published plan, what was their response to you?

Lindsay Nofelt: They gave us a big spreadsheet with a response to each of our comments. It usually says good things, but with no actual—nothing is going to happen. They're just saying “ok.” It comes off as pretty pandering. They don't use regular English. They use edu-speak, what I call edu-babble. And so most people do not understand what they even mean by their sentences, it just gives off a “competent” vibe.

The Bell Ringer: Has your group tried different avenues? You told me once that you’ve tried to support some school board candidates?

Yes. After a while, I thought the only way we're going to go beyond lawsuits and litigation—which seemed sometimes to be the only lever that actually works—was to have a strong school board. That would be the way to make sure that we're talking about the right things and paying attention to the right things.

Are you familiar with the idea of bike shedding? It’s this term also known as Parkinson's Law of Triviality. It's our tendency to spend a disproportionate amount of time on menial and trivial things, and ignore important things. Because it's easier to deal with putting a dishwasher in a school cafeteria to make sure that we're using silverware instead of disposables than it is to address our abysmal scores in reading and math. I feel like it's especially relevant to school boards, because often our time gets agendized in a way that can feel political or ideological, or divisive or small.

Yet if you have a strong school board, they can make the superintendent evaluation be dependent on increasing scores for focal populations. So say, like in Berkeley, you've only got 30% of Black students reading on grade level, and you've got 85% of white kids reading on grade level, an enormous gap that's been shameful to us for 50 years, and it's never been part of the superintendent's evaluation to raise those scores.

If the superintendent’s job was on the line to raise these scores, I guarantee you you'd have better outcomes. This is what they did in Palo Alto—Todd Collins started the California Reading Coalition, and he's a school board member in Palo Alto. They're a very wealthy school district, but he woke up to the reading crisis, he looked at disadvantaged Hispanic students and realized the schools were failing these kids on an enormous level. So the board put it in the superintendent's evaluation that the superintendent had to raise scores for these kids, get them reading. And guess what? It worked.

The Bell Ringer: I think something similar happens with tutoring centers, right? So many wealthy families go to tutoring centers. Their business model depends on getting your kid to read. So what do they do? They use evidence-based methods, because they are most likely to guarantee the best outcome—their business depends on it.

I want to ask you specifically about helping disadvantaged children. It seems to be very high on Berkeley’s priority list.

Lindsay Nofelt: Sure, they say so. But doing so is a whole different matter.

The Bell Ringer: Where’s the disconnect happening? Why is the district refusing to make changes? Is it for philosophical reasons—they are dedicated to curricula like Units of Study? Or is it more like negligence? What’s your observation?

Lindsay Nofelt: The teachers have an innate understanding of the students in front of them within a week. First week of kindergarten, teachers know who is going to be struggling and who is succeeding in school, they can predict the trajectory of these students.

The problem is, there's no mechanism in place to change the trajectory of these students. We're relying on families and parents [to fix the reading issues], and then blaming families and parents when things don't go right. There's this view in the district that’s like, if you say that we should be doing something different or something more, or having more accountability, then you don't trust teachers.

In Berkeley, we care so much about equity. We have a reputation for lifting up the voices and needs of those who have been historically oppressed. We're the birthplace of disability rights, of curb cuts, and here we are saying all the right things about students, but decade after decade never taking advantage of the money, the resources and the time that we have to actually do the right thing. It took a lawsuit for them to look at changing the curriculum from Lucy Calkins, after 14 years of demonstrated failure with that curriculum. Even now, we have teachers who are digging in their heels, and other teachers who are wholeheartedly looking for something different. You've got the spectrum.

There's also no state law forcing teachers to learn the science of learning.

The Bell Ringer: Right. Everything here in Tennessee changed when teachers were required to take the training. It’s only one piece of the puzzle, and we've got other problems, you know, secondary teachers, middle school teachers need it, too—but elementary teachers must take the training now.

I feel like in Berkeley right now, we are still guilty of pandering to those who are not willing to look at how these reading practices have harmed kids. We’re still in that first stage of grief—denial, right? They're using resources that sometimes raise my eyebrows. The book club that they used for professional development the first year of the lawsuit was Shifting the Balance—and that book has some problems, where they're still promoting three-cueing, right?

It hurts when you see practices like three-cueing that have been demonstrated to be so harmful. I'm still working against it in the sixth grade.

My kid is still guessing the word based on the first letter of the word and the context from the rest of the sentence. It's a habit that stays with people for a really long time. It's a battle to unteach something like that when it happens so early in a kid's development.

The Bell Ringer: Is all this why you started Reading for Berkeley?

Lindsay Nofelt: We started Reading for Berkeley because I couldn't put enough public pressure on the school district in my role as a committee member. I put out an email to the different groups that I belonged to and asked if anybody else was into this, and wanted to meet. Luckily, people did, I’m forever grateful about that.

Our goal is threefold. We are trying to provide oversight and accountability for the implementation of the settlement. We read all the reports and then come out with questions and then organize public comment or letter writing so that the district knows that people are paying attention, that people care about this and it cannot be swept under the rug. We have a weekly and monthly meeting with district leadership.

We’re an informational advocacy group, too. We want to inform and engage families in their educational rights, and this is the part that I think makes us the most political, because an informed parent is a terrifying parent.

The Bell Ringer: Parents have played a huge part in spreading the science of reading.

Lindsay Nofelt: If a parent knows their legal rights, federally and statewide, and the magic words, the edu-babble to say in order to activate the system, the parent can start to be that squeaky wheel for their child.

I want my experience being gaslit and told that everything was fine to change. I don't want that to happen anymore, and I want parents to know what's happening in schools. If something is going wrong, I want people to know how to advocate for their own child, because you have to put on your own oxygen mask first.

So we developed a booklet called Actions for Reading Success. It’s 20 pages and it details all the things you can do, things to look for, ways to ask for help and the levers for changing your kids’ educational outcome. It's not easy, of course, but it's there.

One of our first successes, and one that's changed the trajectory for a lot of kids, is one of the consequences of the lawsuit requires a screener for reading difficulties. We didn't have a screener. We had no assessments for reading until third grade.

What we also asked for, and were grateful to get, was a printout of the child's test scores included with the report card every trimester. So now, parents in elementary school get their kids’ report card printed out and handed to them in an envelope with a family report from DIBELS. Our reading scores went up dramatically, like within months of them sharing scores proactively with families. Because if you know in kindergarten, you can actually do something about it at home pretty easily, as long as there's not a reading disability.

The Bell Ringer: Moving forward, are there other roadblocks standing in your way?

Currently, every single school board member has been hand-picked by the teachers’ union. There's a kind of sharing thing happening around here. So our union vice president serves on a neighboring school district school board, and we have the teachers’ union president from the local community college sitting on our school board. So they help each other get seats.

The Bell Ringer: In California, your districts are all really tiny, right? You break them up into small pieces. So is everyone serving all connected to each other?

Lindsay Nofelt: In Berkeley, all the school district elections are “at large,” so you've got an entire city to inform this small district. School board positions are not neighborhood-based. That makes it easier for the unions to help pick the candidates. Because if they are the only voice, and they have successfully hampered all other voices, then it's over.

In 2022 I became fed up with all this. And so I and a bunch of other parents started what we called the Berkeley Parents Union. We decided to try and create another opinion in school board elections, just another point of view. We would take points of view from multiple perspectives of very informed people. The teachers know what they're doing. They're smart, they're involved, you know? And they have a perspective, which is 100% fine.

The problem is it’s the only perspective. We registered as a PAC [political action committee], because the election laws in Berkeley are very restrictive.

We tried to organize, and immediately a smear campaign from a current school board member started, and he used his email list of thousands of people to target our group. We had refused to come out as to who we were exactly, because in the past, when parents had tried to organize, people called CPS on parents who dared to speak up. There are other ways that kids and families are being targeted. So we decided to go with: please just trust that we are actually parents, that we are involved and that we care and that our goals are all the same quality education for all public school students.

But instead, the email that went out said that we were a bunch of foreign, right-wing Republicans taking money from the Walton family, which in Berkeley is like a death knell.

The Bell Ringer: Had you taken any outside money?

Lindsay Nofelt: No, we did not. But the campaign did hurt people’s feelings so much, and created so much unnecessary division and angst. It feels bad when you’re personally attacked as a non-public figure. The Parents Union ultimately failed.

What happens then is that candidates who would be good for kids are reluctant to put themselves forward. The person we supported as the Berkeley Parents Union in 2022 declined to run again, and other people just don't want to put themselves out there, even if we think that they have a good chance of winning. There was a woman who made her career out of giving teachers grants we thought would be so good to run, and she said, “Not even with a 10-foot pole. No, thank you.”

The Bell Ringer: What’s next for you?

Lindsay Nofelt: We just continue to push in whatever ways we can. We give ourselves grace when we can't, because this is volunteer work, and sometimes stuff happens and you have to be able to punch in and punch out as things happen in life. This is what's so frustrating—that's what they're hoping for, because they know we’re all a bunch of volunteers, and they know that the system can out run you.

They certainly can. But I've told them face-to-face that this is a 10-year project for me, and I'm only in year five. Even if you don't hear from me for a month because I'm dealing with some other thing, I'll be back. Don't you worry.

* Every issue of The Bell Ringer comes to you in an email, but you can also find the entire archive at The Bell Ringer website.

* For newsy comments on education issues, talks with teachers, etc, and contentious conversations about stuff like—what exactly do we mean by inquiry instruction?—just like in the heyday of Twitter, you can follow me on Blusky! That’s where the majority of my edu-curiosity is based at the moment. Come find me and let’s chat.

* Last but not least, If you are enjoying this newsletter, please like this post and share with your teachers and network. That’s how the word gets out about the research on learning.

Great article, Holly! Sounds so familiar! Thank you!

Great interview. Just a quick comment: I think there may be crossed signals regarding MTSS. Did this parent ever consider that MTSS could be yet more 'edu-babble'? Or at least, maybe that the parents and the district are talking past each other on this issue because it means different things to both groups?

Just something to consider. Thanks for the real insight.